In March 1985

In 1985, London was a vibrant hub of various subcultures, each with its distinct fashion, music, and attitude. The city was a melting pot of creativity and rebellion, and subcultures, such as the New Romantic movement, provided many young people a profound sense of belonging and identity, which resonates even today.

One of the most prominent subcultures of the time was the New Romantic movement, characterised by flamboyant and eccentric fashion, influenced by historical and fantastical elements. This subculture, with its close association with the Blitz Club in Covent Garden, where Boy George and Duran Duran were regulars, left an indelible mark on popular culture, a testament to its enduring influence.

Amid the fashion evolution from New Romantics to Grunge in March 1985, The Face magazine showcased a striking fashion story that introduced a new aesthetic called Buffalo. This unique style combined Native American headdresses, Savile Row suits, bovver boys’ flight jackets, and Doc Martens, creating a rebellious and edgy look. The article featured a group of stunning black and mixed-race models, including a 14-year-old Naomi Campbell, captured by Jamie Morgan and styled by Ray Petri. Described as 'street-real' by Vogue editor Edward Enninful, the Buffalo style was heavily influenced by punk and the vibrant atmosphere of Ladbroke Grove. Notably, singer Neneh Cherry popularised the attitude associated with this style in her 1988 hit, 'Buffalo Stance'.

Post-punk and goth subcultures also thrived in London during this period. These subcultures embraced a darker, more introspective aesthetic, and bands like The Cure, Siouxsie, and the Banshees gained popularity.

Furthermore, the hip-hop and breakdancing scene also made waves in London, especially in urban areas. The influence of American hip-hop culture was evident in the fashion, music, and dance styles of young Londoners.

Eighties British subculture

The British subculture has a rich and diverse history, with various movements and styles emerging over the years. One notable example is the subculture of the 1980s, which was heavily influenced by figures such as the Burmese-British model and artist Barry Kamen and his older brother Nick. This period saw the rise of the Buffalo aesthetic, characterised by a unique blend of fashion, music, and attitude.

At the heart of the movement was the personal journey of the Burmese-British model and artist Barry Kamen (1963-2015), who, along with his older brother Nick (1962-2021), came to define the Eighties British subculture. Kamen's upbringing as the youngest of eight children born to Burmese parents in Harlow, Essex, during a time ofracial unrest, shaped his unique perspective and influenced the Buffalo aesthetic.

The Buffalo subculture was not just a trend but a significant movement that embraced diversity and challenged societal norms. It celebrated individuality and selfexpression, often incorporating elements of different cultures and traditions. This subculture was a powerful form of resistance to the status quo and played a pivotal role in shaping the cultural landscape of the time.

The British subculture of the 1980s, including the Buffalo movement, continues to influence art, fashion, and music today. Its legacy reminds us of the power of creativity and the enduring impact of subcultures on mainstream culture. Persona influenced the Buffalo aesthetic.

The tough stance of Buffalo

The British fashion movement known as Buffalo Stance emerged in the late 1980s and was heavily influenced by the time's underground music and club scenes. The movement was characterised by its bold and eclectic mix of styles, combining hip-hop, punk, and DIY fashion elements. Buffalo Stance was all about self-expression and individuality, embracing a 'do-it-yourself' ethos and rejecting the mainstream fashion norms of the era. Buffalo Stance was more than just a fashion trend. It was a movement that challenged conventional beauty standards, celebrated diversity, and embraced street culture. Drawing inspiration from urban street style, Buffalo Stance incorporated oversized silhouettes, vibrant colours, and clashing patterns. It was a bold and unapologetic rejection of the polished and glamorous aesthetic that reigned in the fashion industry at the time. The Buffalo Stance movement was not just a fashion trend, but a cultural phenomenon. Key figures like stylist Ray Petri and the Buffalo collective played a pivotal role in shaping its aesthetic and attitude. Their work in fashion editorials, music videos, and street culture was instrumental in popularizing the Buffalo Stance look and ethos. Overall, Buffalo Stance represented a radical departure from the mainstream fashion of the 1980s, embracing a raw, unrefined, and authentic aesthetic that continues to influence fashion and subcultures to this day. However, e tough stance of Buffalo was balanced by sensitivity and kindness — and these were the qualities that Kamen became known for. As his wife, the author and former model Tatiana Strauss, recalls, ‘He had such a gentle, spiritual nature and a way of giving the other person his full attention that he nearly always managed to make friends with his enemies.’ The fashion designer Stella McCartney remembers thinking, ‘What a rare creature he seemed to be in this sea of humans we all encounter’.

Source: https://www.barryboyart.com

Strauss met Kamen in the early Nineties while on a fashion show at Leeds Castle in Kent. ‘He was sitting on the grass, drawing,’ she says. ‘I soon realised it was an obsession.’ Kamen’s father, who died when Barry was 13, had trained as a draughtsman and passed this rigorous discipline on to his son.

Kamen was among the male models who walked for Jean Paul Gaultier’s women’s show in Paris in 1989 — with painted torsos rather than outfits —but years later found himself on the other side of the camera, styling campaigns for Comme des Garçons and Puma.

Art

Barry Kamen was a multi-talented artist known for his work as a work as a painter, fashion designer, and musician. A unique blend of bold colours, striking imagery, and a sense of urban grit characterised Kamen's artistic style. His paintings often reflected elements of street culture and the human experience, capturing the raw energy of the time. In addition to his visual art, Kamen's contributions to fashion and music cemented his status as a true creative force. His legacy continues to inspire and influence artists across different disciplines. Art remained Kamen's first passion, and with the encouragement of his mentor,

Art remained Kamen's first passion, and with the encouragement of his mentor, Ray Petri, he began exhibiting his work. One of his paintings appeared on the album sleeve of UB40's Labour of Love II. Then, following his first show at Gaultier's studio in Paris in 1989, he attracted a loyal group of collectors, among them Kate Moss, the photographer Jean-Baptiste Mondino, and the fashion designers Azzedine Alaïa, Helmut Lang, and Stella McCartney. 'It's the confidence of the stroke, it's the delicacy of the subject matter—all of that, together with Barry's personality, is something very rarely found, I think, in an artist's work,' McCartney says. Kamen's artistic journey

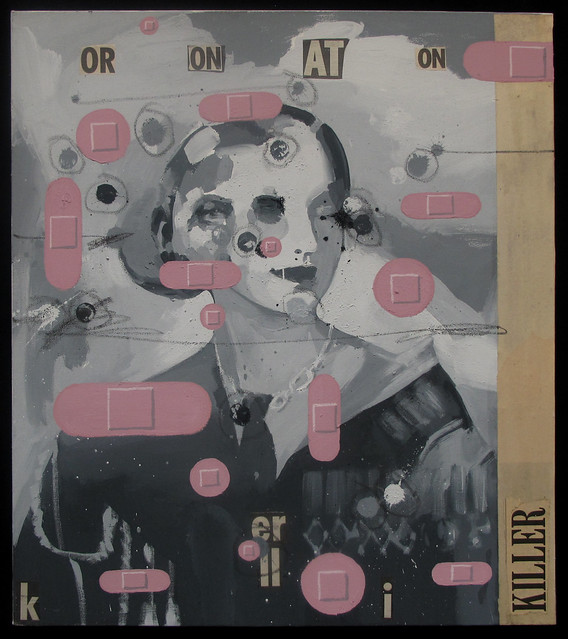

Kamen's artistic journey took a new turn when he delved into the world of Old Master paintings at the National Portrait Gallery in London. 'Just as Buffalo was about infusing power with an attitude, Barry began experimenting with 18th- and 19th-century portraiture, examining how power is conveyed through clothing and posture,' explains Kamen's close friend, artist Glen Erler. This intellectual exploration added a new dimension to Kamen's work, further enriching his artistic repertoire.

OR ON AT ON

Source: https://www.barryboyart.com

The coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953 was a historic event that captivated people around the world. Commemorative items made for this occasion, including printed materials featuring Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, reflected the grandeur and significance of the event. These printed materials, such as books, newspapers, and magazines, depicted the royal couple in regal attire, showcasing their roles as the new monarch and consort.

After years of exploring abstract art, the artist began a new portraiture series, ‘Is It’, in 2006. A notable work from this series, titled 'OR ON AT ON (Portrait of Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh)' created in 2010, is now being presented in the First Open: Post-War and Contemporary Art Online exhibition until March 9, 2023, marking a significant milestone in the artist’s career.

Based on a black-and-white lenticular postcard of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip that was produced for the 1953 coronation, the piece was created. The royals are shown in a state of metamorphosis, their features shape-shifting into one another. The picture is embellished with painted sticking plasters that conceal parts of the image. Barry was fascinated by the way royalty declared itself in paint. 'As a biracial man in Britain, he was dealing with that,' says Strauss.

Killer

Source: https://www.barryboyart.com

Dadaism, an art movement of the European avant-garde in the early 20th century, was a direct reaction to the horrors of World War I. It was embraced by artists and writers such as Marcel Duchamp, Tristan Tzara, and Hugo Ball, who rejected logic and reason. In their pursuit to shock and provoke, these Dadaist figures often used absurdity and non-traditional materials. This movement, with its significant impact on the development of modern art, continues to shape and influence contemporary artists today, underscoring its enduring significance.

Erler vividly recalls Kamen’s love of Dadaist wordplay, Jamaican patois. ‘He saw words almost as living things that moved and changed — he would cut words out, erase them and constantly use them in his paintings.’ This innovative use of language by Dadaist artists adds a layer of intrigue to their unconventional approach.

‘Many of the words Barry painted came from Buffalo,’ says Strauss. ‘That time had a huge influence on his practice.’ Kamen considered himself a product of colonialism, and the legacy of British imperialism, which had a significant presence in Buffalo, was not lost on him. However, Strauss describes Kamen’s view of the monarchy as ‘ambivalent’, reflecting the complex relationship between the artist and the historical context of his work.

Photo by Jamie Morgan

Erler recalls the artist constantly experimenting: ‘I remember being in his studio in West London and he would be drawing these faint circles repeatedly, they were just beautiful. He was always making; he had this singular focus.’

First appearance:Buffalo stance: how artist Barry Kamen became the face of Eighties British youth culture (https://www.christies.com/en/stories/how-barry-kamen-became-the-face-of-british-youth-culture-11cfb432bf564d8c8d7164c7d3811d0e)